In the Bible, unleavened bread is called “unleavened bread,” whereas leavened bread is simply called “bread.” The Jews at that time would have understood this as would have the early Christians. It says that “He took bread,” meaning leavened bread; and the Christians, being first instructed by the Apostles and then reading in the Gospels some time later, implemented this.

At the Mystical Supper, it is obvious that our Lord was changing things, to tie the Passover meal with its fulfillment, the Eucharist. One of those changes, obviously, was using leavened bread instead of unleavened, or at least leavened in addition to unleavened. The world was empty and devoid of grace before Christ, as is symbolized by the flatness of the unleavened bread, but later filled with the glory of His Resurrection, as is symbolized by the leavened bread. Christ made the change, and the Church followed through on it.

The word for unleavened bread in Greek is AZYMOS it is used in the Greek New Testament nine times: Mt.26:17; Mk.14:1,12; Lk.22:1,7;Ac.12:3; 20:6; 1Cor.5:7,8.

The word for leavened bread is ARTOS it is used 97 times in the Greek New Testament.

The passages where they are relevant for the Mystical Supper are;

Now as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and after blessing it broke it and gave it to the disciples, and said,

“Take, eat; this is my body.”

– Mt. 26:26; Mk.14:22; Lk.22:19;24:30,35; 1 Cor.10:16,17 (twice);11:26,27,28.

In all these places, the writers never say Jesus took AZYMOS and blessed it, they write that Jesus took ARTOS, common ordinary leavened bread.

Here is a quote from the book Bread and Liturgy by George Galavaris:

Here is a quote from the book Bread and Liturgy by George Galavaris:

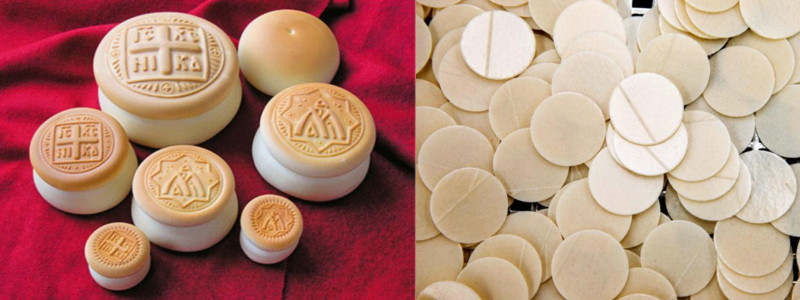

The same baking method and ovens were used by the Christians for both their daily bread and that which was to be used in worship. It must be made clear that (contrary to practices today in the West) in the Early Christian centuries and in all eastern rites through the ages, except in the Armenian church, the bread used for the Church did not differ from ordinary bread in substance. From the beginning leavened bread was used. Even the Armenians before the seventh century and the Maronites before their union with Rome in the twelfth century used leavened bread. The practice of using unleavened bread for the Eucharist was introduced to the West much later. Among the earliest written accounts is that given by Alcuin (A.D. 798) and his disciple Rabanus Maurus. After this the altar bread took the light, wafer like form, achieved with pressing irons, so common today. (Galavaris, Bread and Liturgy, p. 54).

The adjectival form Azymite was used as a term of abuse by Orthodox Christians against Latin Rite Christians. The Orthodox Church has continued the ancient Eastern practice of using leavened bread for the Lamb (Hostia ‘victim’ in Latin) in the Eucharist. After serious theological disputes between Rome and the churches of the East, Latin use of unleavened bread, azymes, for the Eucharist—a point of liturgical difference—became also a point of theological difference between the two, and was one of several disputes which led eventually to the Great Schism between Eastern and Western Christianity in 1054.

Here is a quote from a Latin priest and professor of theology at the university of Vienna named Johannes H. Emminghaus:

Here is a quote from a Latin priest and professor of theology at the university of Vienna named Johannes H. Emminghaus:

In the Latin Rite, the bread for the Eucharist has been unleavened since the eighth century; that is, it is baked of flour and water without yeast. At the Last Supper, Christ probably took this kind of bread (mazzah), which was interpreted in the Passover memorial as a “bread of affliction,” the bread of nomadic shepherds who had no homeland of their own.

During the first millennium of Church history, however, it was the general custom in both East and West to use normal “daily bread,” that is, leavened bread, for the Eucharist; the Eastern Churches still use it and usually have strict prohibitions against the use of unleavened bread (or “azymes”).

The Latin Church, for its part, regards the question as of little importance, since at the Council of Florence, which sought to reunite East and West (1439), the difference in custom was simply acknowledged and accepted. (Rev. Johannes H. Emminghaus, The Eucharist: Essence, Form, Celebration, p. 161).

Here is a quote from a Jesuit priest and professor of Theology at the University of Innsbruck:

In the West, various ordinances appeared from the ninth century on, all demanding the exclusive use of unleavened bread for the Eucharist. A growing solicitude for the Blessed Sacrament and a desire to employonly the best and whitest bread, along with various scriptural considerations—all favored this development.

Still, the new custom did not come into exclusive vogue until the middle of the eleventh century. Particularly in Rome it was not universally accepted till after the general infiltration of various usages from the North. In the Orient there were few objections to this usage during olden times. Not till the discussions that led to the schism of 1054 did it become one of the chief objections against the Latins.

At the Council of Florence (1439), however, it was definitely established that the Sacrament could be confected in azymo sive fermentato pane. Therefore, as we well know, the various groups of Orientals who are united with Rome continue to use the type of bread traditional among them. (Rev. Joseph A. Jungmann, SJ., The Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. II, p. 34).

In other words, the use of unleavened bread with the round host-style bread came from the forests of Germany. In the ninth century the use of unleavened bread had become obligatory in the West, while the Orthodox continued the exclusive offering of leavened bread. The issue became divisive when the provinces of Byzantine Italy which were under the authority of the Patriarch of Constantinople were forcibly incorporated into the Church of Rome following their invasion by the Norman armies. At this time the use of unleavened bread was forced upon the Orthodox of southern Italy.