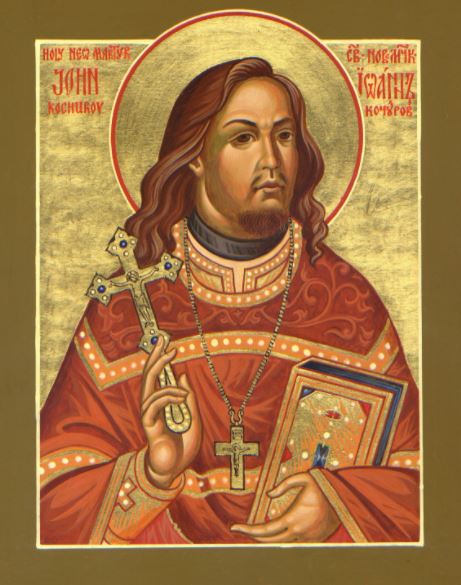

St. John Kochurov

Missionary to America and First Hieromartyr under the Bolshevik Yoke

On October 31, 1917, in Tsarskoye Selo, a bright new chapter, full of earthly grief and heavenly joy, was opened in the history of sanctity in the Russian Church: the holiness of the New-Martyrs of the twentieth century. The opening of this chapter is linked to the name of the Russian Orthodox shepherd who became one of the first to give his soul for his flock during this twentieth century of fighters against God: Archpriest John Kochurov.

Father John Kochurov was born on July 13, 1871, in the village of Bigildino-Surky of the district of Danky in the Ryazan region, to a pious family of many children. His parents were the priest Alexander Kochurov and his wife Anna. Father Alexander Kochurov served almost all his life in the Church of Theophany in Bigildino-Surky village in the Diocese of Ryazan from the moment of his ordination on March 2, 1857, and having combined all those years of service in the parish with the fulfillment of his obligations as a teacher of the God’s Law in the Bigildin’s public school, imprinted in the consciences of his sons, and particularly in that of John, the most spiritually sensitive of them, a radiant image of the parish priest, full of deep humility and high inspiration.1

Fr. John’s upbringing, being based on the remarkable traditions of many generations of the clergy and bound with the people’s natural following after Orthodox piety, foretold his setting out on the path of preparation for pastoral service. Father John’s study — initially at Danky Theological School and afterwards at Ryazan Theological Seminary — was marked not only with outstanding success in the mastery of theological and secular disciplines, but with remarkable examples of Church piety which he demonstrated during a time when the everyday life of a provincial theological school was not always spotless in the moral sense.

The future Father John successfully graduated in 1891 from the Theological Seminary in Ryazan. Having passed the entrance exams for the Saint Petersburg Theological Academy, he became a student at one of the best theological schools in Russia.2

During the period of Fr. John’s study at the Saint Petersburg Theological Academy, his propensity to regard theological education as a preparation primarily for future service as a parish priest became clearly defined, while at the same time, Fr. John already during his student days coupled the possibility of his service as a parish priest with that of missionary activity, in which he saw the embodiment of the ideal of the Orthodox pastor. After his graduation from Saint Petersburg Theological Academy with the distinction of a true student, Fr. John was sent, in accordance with his long desire for missionary service, to the Diocese of the Aleutians and Alaska.3

Not long after his marriage to Alexandra Chernyshova, Fr. John’s arrival in protestant America put him in touch with a life dissimilar in many respects from his accustomed life in Orthodox Russia. For his first sojourn in the U.S.A. Fr. John arrived in New York, which with its mundane ways was so different from the spiritual life of the Russian cities. Not having yet learned the English language, Fr. John, thanks to the brotherly support of the New York Orthodox community — at that time of modest size — did manage to adjust himself to the life of the country, till then unknown to him, without any particular psychological or other complications. It must be noted that Church life in the Diocese of Alaska and the Aleuts was very different in character from that in other parts of the country, which was vast in its territory but rather small in the number of clergy. Specifically, the Russian Orthodox missions in Northern California, on the Aleutian Islands, and in Alaska had at that time already existed for about a hundred years, and Church life was conducted on a foundation of rather numerous parish communities which possessed significant financial resources, having become accustomed over several generations to life in America. But Orthodox life in the rest of the country was only being initiated, and it required a great deal of evangelical activity by the clergy to create normal Orthodox parishes within the multinational and multiconfessional local population. It was precisely to that part of the diocese that Fr. John was destined to be sent when he was ordained to the dignity of a priest on August 27, 1895, by the Most Reverend Nicholas, Bishop of Alaska and the Aleuts.4

The beginning of Fr. John’s parish service was associated with the opening, by Bishop Nicholas, of the Orthodox parish in Chicago in 1892. Assigned in 1895 by order of the Holy Synod to be a parish priest at Saint Vladimir’s Cathedral in Chicago, Fr. John was put in touch with a parish life that was strikingly different from the Orthodox parishes in Russia, which were organized and rooted in a living tradition many centuries old. Being a lonely island of Orthodox Christian life, remotely situated many hundreds of miles from the other scattered Orthodox parishes in North America, Saint Vladimir’s Church in Chicago,5 together with the Church of the Three Hierarchs in the town of Streator with which it was affiliated, in the less than three years of its existence still had not managed to become formed as a parish in the full sense of this word, and it indeed required heroic labors from the young Fr. John to be established in a proper way.

The beginning of Fr. John’s parish service was associated with the opening, by Bishop Nicholas, of the Orthodox parish in Chicago in 1892. Assigned in 1895 by order of the Holy Synod to be a parish priest at Saint Vladimir’s Cathedral in Chicago, Fr. John was put in touch with a parish life that was strikingly different from the Orthodox parishes in Russia, which were organized and rooted in a living tradition many centuries old. Being a lonely island of Orthodox Christian life, remotely situated many hundreds of miles from the other scattered Orthodox parishes in North America, Saint Vladimir’s Church in Chicago,5 together with the Church of the Three Hierarchs in the town of Streator with which it was affiliated, in the less than three years of its existence still had not managed to become formed as a parish in the full sense of this word, and it indeed required heroic labors from the young Fr. John to be established in a proper way.

Beginning his work at the parish of Chicago and Streator, which was rather small and multinational in its constituency, Fr. John nourished these people, who were representatives of a rather poor class of immigrants, in the Orthodox confession. He was never able to be supported in his work by a sound parish community having at its disposal sufficiently large material means. In one of his articles, written in December 1898, Fr. John gave the following vivid description of the Chicago-Streator parish community: “The Orthodox parish of Saint Vladimir’s Church in Chicago consists of a small number of the original Russians, Galician and Hungarian Slavs, Arabs, Bulgarians, and Aravians. The majority of the parishioners are working people who earn their bread by toiling not far from where they live, on the outskirts of the city. Affiliated with this parish in Chicago is the Church of the Three Hierarchs in the city of Streator. This place, and the town of Kengley, are situated ninety-four miles from Chicago, and they are famous for their coal mines. The Orthodox parish there consists of the Slovaks who work there who have been converted from the Unia.”6

The unique characteristics of the Chicago-Streator parish community demanded of Fr. John a deft combination of pastoral-liturgical skills, with missionary ones. These abilities would permit him not only to stabilize the membership of his parish community spiritually and administratively, but to enlarge his flock continually by means of conversions, or by the return to Orthodoxy of the ethnically diverse Christians living in Illinois. Already during the first three years of Fr. John’s parish service 86 Uniats and 5 Catholics were added to the Orthodox Church,7 bringing the number of permanent parishioners up to 215 men in Chicago, and 88 in Streator. There were two functioning church schools affiliated with the parishes, with more than 20 pupils enrolled in them. The course consisted of Saturday classes during the school year, and daily classes during the school vacations. 8

In his work, Fr. John continued the best traditions of the Russian Orthodox Diocese in North America. He organized, in Chicago and Streator, the Saint Nicholas and Three Hierarchs Brotherhoods, which established a goal of setting up a program of social and material mutual aid among the parishioners of the Chicago-Streator parish, as members of the Orthodox Mutual Aid Society.9

Father John’s abundant labors for building up a healthy, flourishing parish life in the communities entrusted to him did not hinder him from fulfilling other important diocesan responsibilities that were laid upon him. So it was that, on April 1, 1897, Fr. John was appointed to be one of the members of the newly created Censorship Committee of the Diocese of Alaska and the Aleutians on texts in the Russian, Ukrainian, and English languages,10 and on May 22, 1899, Fr. John was appointed Chairman of the Board of the Mutual Aid Society11 by a decree of Tikhon, Bishop of Alaska and the Aleutians, who had recently arrived in the diocese. The varied labors of Fr. John were soon rewarded; after just the first years of his pastoral service, he received the marks of priestly distinction from the Most Reverend Bishop Nicholas.12

A significant obstacle to the normal functioning of the Church liturgical cycle at the Chicago-Streator parish was the condition of the buildings, which were unfit for the purpose. Saint Vladimir’s Church in Chicago occupied a small part of a rented edifice located in the southwestern part of the city. On the ground floor of the house the church itself was separated by a wall from the kitchen and a room where an attendant lived. On the first floor there were several small rooms which were occupied by Fr. John together with his family and by the church Reader. The church of the Three Hierarchs in Streator employed the lobby of the Russian section of the Chicago World Exhibition [the Columbian Exposition of 1892—Ed.].13

The assignment of Bishop Tikhon, the future Patriarch of Moscow, to the Diocese of Alaska and the Aleutians on 30 November, 1898, was especially significant for the resolution of problems of church life in the parish entrusted to Fr. John. Zealously fulfilling his hierarchical obligations, Bishop Tikhon already during the first months of his leadership of the see managed to visit practically all the Orthodox parishes scattered around the vast territory of the Diocese of Alaska and the Aleutians, in an effort to discern the most fundamental needs of the diocesan clergy. Arriving in Chicago for the first time on April 28, 1899, Bishop Tikhon gave his archpastoral blessing to Fr. John and to his flock, and by the next day he had already inspected a plot of land proposed as the site where the new church — so necessary for the parish in Chicago — would be constructed. On April 30, Bishop Tikhon visited the Three Hierarchs Church in Streator and served the vigil service at Saint Vladimir’s Church in Chicago. On the following day, after serving the Divine Liturgy, he approved the minutes of the meeting of the committee for the construction of the new church in Chicago, which was chaired by Fr. John.14

The limited financial resources of the Chicago-Streator parish, where the people being ministered to were primarily poor, did not permit Fr. John to begin the construction immediately. And since more than five years had already passed since the time of Fr. John’s arrival in North America, his great desire to visit his beloved Orthodox Russia for at least a brief time prompted him to submit an application to Bishop Tikhon requesting leave for the journey to his motherland.

Being above all mindful of the needs of the parish entrusted to him, Fr. John decided to use the vacation granted to him from January 15 till May 15, 1900, to collect money in Russia which would allow the Chicago parish to commence construction of the new church building and of the first Orthodox cemetery in the city.15 Successfully combining his journey to his motherland with significant fundraising for the parish, Fr. John soon after his return from leave embarked on the construction of the church, with Bishop Tikhon arriving on March 31, 1902, for the ceremony of the laying of its foundation.16

With true pastoral inspiration combined together with sober, practical record-keeping, Fr. John managed the construction of the new church, which was finished in 1903, requiring a very significant sum of money for that time, fifty thousand dollars.17 The consecration of the new temple, which was named in honor of the Holy Trinity, was performed by Bishop Tikhon, and it became a real festivity for the whole of the Russian Orthodox diocese in North America. Two years later, in greeting Fr. John on the occasion of his first ten years of service as a priest in the Church, the highest praise went to his careful pastoral labors in the construction of the Holy Trinity Church, which had become one of the most remarkable Orthodox churches in America: “The year has been filled with the most vivid of impressions, sometimes agonizing, sometimes good. A year of endlessly trying fund-raising in Russia, a year of sleepless nights, worn-out nerves, and countless woes — and here is the testimonial of your care: a temple made with hands, in the image of a magnificent Russian Orthodox temple, shining with its crosses in Chicago, and the peace and love not made with hands that are springing up in the hearts of your flock!”18 For his inspiring labors, Fr. John, thanks to the intercession of Bishop Tikhon, was awarded the Order of Saint Anna of the Third Degree, on May 6, 1903. 19

Zealously fulfilling his numerous obligations as a parish priest, he was the only priest there during the first nine years of his service in the parishes of Chicago and Streator. At the same time, Fr. John continued to participate actively in resolving various issues in the life of the North American diocese. In February 1904, Fr. John was assigned as a chairman of the Censor Committee of the Diocese of Alaska and the Aleutians, where he had already participated as a member of the council for seven years.20 In June 1905, he was an active participant in the preparatory meetings of diocesan clergy, held in Old Forge [Pa.] under the guidance of Bishop Tikhon, where issues were discussed in connection with preparation for the first Council in the history of the Diocese of North America and the Aleutians. It was in the solemn atmosphere of the sessions of this Council, on July 20, 1905, that Fr. John’s first decade of priestly service was celebrated, the actual date of the anniversary being August 27.

In Saint Michael’s Church in Old Forge, before a large group of diocesan clergy presided over by the Most Reverend Raphael, Bishop of Brooklyn, Fr. John was awarded a gold pectoral cross, and the speeches offered a perceptive and thoroughly objective description of the whole period of Fr. John’s pastoral service in North America. “Directly after your study at seminary, having left the motherland, you came to this strange land to expend all your youthful energy, to devote all your strength and inspiration for that holy concern to which you were attracted in your vocation. A hard legacy was left for you: the church in Chicago was located then in an untidy church setting, in a wet, half-ruined building, the parish with its loosely defined parish membership scattered over the huge city with a heterodox population torn asunder by the wild beasts — all that could fill the soul of a young laborer with great confusion, but you bravely accepted the task of selecting a precious spark from the pile of rubbish, to fan the sacred fire into a small group of faithful! You were forgetful of yourself: calamities, illnesses, the poor location of your house, with its ramshackle walls, floors, and cracks that gave open access to the outer elements, with destructive effects on your health, and the health of your family members….Your babies were sick, your wife was not quite healthy, and bitter bouts of rheumatism seemed to wish to destroy your confidence, to exhaust your energy. . . . We greet you, remembering another of your good deeds, the performance of which is plaited as an unfading laurel in the crown of honor of your decade of sacred service: we have in mind here your sacrificial service in the office of Chairman of our beloved Mutual Aid Society, in the office of Censor to our enlightening missionary publishing house, and in spreading wide our evangelical efforts — organizing the parishes in Madison [Ill.] and Hartshorne [Okla.]. To complete your tribute, let us mention another circumstance, which magnifies the valor of your labor and the grandeur of its results. The remoteness of your parish in Chicago has torn you from your bonds with your colleagues in America, depriving you during these years of the chance to see your brother-pastors . . . You were bereft of that which for the majority of us adorns the missionary service through which we pass. How touching, and how great a degree of isolation was yours, is witnessed by the fact that you had to baptize your children yourself, because of the absence of the other priests around you . . . Let this Holy Cross we present serve you as a sign of our brotherly love, and the image of our Lord’s Crucifixion on it permit you to accept the hardships, misfortunes, and sufferings that are so often met with in the life of a missionary priest, and let it encourage you to more and more labors for the glory of the Giver of Exploits and the Chief Shepherd, our Lord Jesus Christ.”21

Less than a year after the celebration of the tenth anniversary of Fr. John’s priestly service he was granted by the highest Church authority one of the most honorable priestly orders, which deservedly crowned his genuine exploits in the Diocese of North America and the Aleutians. By order of the Holy Synod on May 6, 1906, Fr. John was elevated to the dignity of Archpriest.22

Thus, there began a qualitatively new period in Fr. John’s service: having become one of the most respected archpriests of the Diocese thanks to his outstanding pastoral work in his parish and in diocesan administrative activities, Fr. John, at the initiative of Bishop Tikhon who valued him highly, became more and more deeply involved in resolving the most pressing issues of diocesan administration. In May 1906, Fr. John was appointed dean of the New York area of the Eastern States,23 and in February 1907, he was destined to be one of the most energetic participants of the first North American Orthodox Council in Mayfield, which dealt with the rapidly increasing conversions within the Diocese of North America and the Aleutians in the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church in America, which was the basis on which the Orthodox Church in America was later founded.

During the period 1903-1907, the Chicago-Streator parish, built by his labors, was transformed into one of the most self-sufficient and flourishing diocesan parishes. But however successful the external circumstances of Fr. John’s service in North America may have seemed, his deep, fervent homesickness for his beloved Russia, which he had only seen once for a leave of several months in recent years, and the necessity of providing his three elder children with an undergraduate education in Russia, compelled Fr. John to think about the possibility of continuing his priestly ministry in his native Russian land. A rather significant circumstance furthering Fr. John’s submission of an application for transfer back to Russia was the insistent request of his elderly and seriously ailing father-in-law, who was a clergyman of the Diocese of Saint Petersburg, and who dreamt of handing over his parish to the guidance of such a deserving priest as Fr. John had shown himself to be. In accordance with his application, Fr. John received, on May 20, 1907, a release from his service in the Diocese of North America and the Aleutians, whereupon he began preparing himself for his move back to Russia. The week before their departure, however, Fr. John and his family had to bear some sudden startling news from Russia: Matushka Alexandra’s beloved parent had succumbed in advance of their return. In July 1907, leaving the Chicago-Streator parish which was so dear to his heart, and where he had given twelve years of missionary service, Fr. John set out for the unknown future that awaited him in his motherland, where he would spend the rest of his priestly service from thenceforth.24

Fr. John’s return to Russia in the summer of 1907 signified for him not only the beginning of his service in the Diocese of Saint Petersburg — familiar to him from his student years — but it challenged him with the need to apply the pastoral skills he had earlier acquired in America in the field of theological education. By order of the Saint Petersburg Church Consistory, in August 1907 Fr. John was assigned to the clergy of Holy Transfiguration Cathedral in Narva, and beginning August 15, 1907, he began to perform his duties as a teacher of Law in the male and the female gymnasiums in Narva.25 By order of the chief of the Saint Petersburg Area Educational Department, effective October 20, 1907, Fr. John was confirmed in his service in the male gymnasium as a teacher of God’s Law [this Russian term refers to the totality of Orthodox teaching — Ed.] and was a hired teacher of the same subject in the female gymnasium of Narva, which became the main sphere of his Church service for the next nine years of his life.26

The common way of life in small, provincial Narva, where the Russian Orthodox inhabitants consisted of scarcely half the population, brought back to Fr. John in some measure the atmosphere familiar to him in America, where he performed his pastoral service in a social environment permeated with heterodox influences. However, the circumstances of his work as a teacher of God’s Law in two secondary schools where the Russian cultural element and Orthodox religious ethos indisputably dominated, permitted Fr. John to feel that he was breathing an atmosphere of Russian Orthodox life reminiscent of his childhood.

Father John’s teaching load as a rule consisted in those years of sixteen hours a week in the male gymnasium and ten hours in the female one. This required of him a fairly significant effort, taking into account that to teach God’s Law in the different classes, because of the breadth of the subject, necessitated that a teacher be familiar with various matters of theological as well as of a mundane character.27 However, inasmuch as the twelve years of his labors at the Chicago-Streator parish had transformed Fr. John from an inexperienced beginner into one of the most authoritative pastors in the diocese, his nine years service of teaching God’s Law — not marked by any spectacular events, but filled with concentrated work in imparting spiritual enlightenment, was one in which Fr. John became a most conscientious practical Church teacher and learned Orthodox preacher. After just five years of teaching Divine Law in the Narva schools, Fr. John was awarded the Order of Saint Anna, Second Degree,28 on May 6, 1912, and after another four years Fr. John’s achievements in the field of theological education were celebrated by his being awarded the order of Saint Vladimir, Fourth Degree, which — added to numerous Church and State awards — gave the deserving archpriest the right of receiving the title of nobility.29

The manifest successes of Fr. John in his activity as a teacher during all these years were supplemented by his joy at the fact that all of his four elder sons, while studying in Narva gymnasium, had the opportunity to receive their spiritual upbringing under his immediate guidance.30

The manifest successes of Fr. John in his activity as a teacher during all these years were supplemented by his joy at the fact that all of his four elder sons, while studying in Narva gymnasium, had the opportunity to receive their spiritual upbringing under his immediate guidance.30

However, along with undeniable advantages of this new period of the pastoral service of Fr. John, after his return to his fatherland following many years of absence, there still existed a circumstance which could not help but burden the heart of such a genuine parish pastor as Fr. John was for the whole of his life. Being only attached to the Holy Transfiguration Cathedral in Narva, and not being a member of its staff clergy, Fr. John, because of the peculiarity of this situation, on account of his fulfilling his duties as a teacher of Gods Law at the gymnasium, was deprived not only of the chance to lead, but even to participate fully in the parish life of Holy Transfiguration Cathedral in Narva. Only in November of 1916, by order of the Saint Petersburg Church Consistory, was Fr. John assigned as a parish priest to the vacant second position at Saint Katherine’s Cathedral in Tsarskoye Selo,31 whereby his dream of resuming service as a parish pastor in the motherland was fulfilled.

Tsarskoye Selo, which had become the remarkable incarnation of a whole epoch in the history of Russian culture, happily combined in itself the qualities of a quiet provincial town with those of the resplendent capital of Saint Petersburg. Saint Katherine’s Cathedral occupied a special place in the town; of the parish churches there, which were predominantly parishes of the imperial court and of the military, it was the largest. In becoming a member of the clergy at Saint Katherine’s Cathedral, and taking up residence there together with his matushka and five children (the oldest son, Vladimir, was at the time fulfilling his military service),32 Fr. John received, at last, his longed-for chance to be immersed fully in the life of a parish priest in one of the most notable churches of the Saint Petersburg diocese. Having been warmly and respectfully received by the flock of Saint Katherine’s, Fr. John, from the first months of his service there, showed himself to be zealous and inspiring not only as a celebrant of the divine service, but also as an eloquent and well-informed preacher, who gathered under the eaves of Saint Katherine’s Cathedral Orthodox Christians from all around the town of Tsarskoye Selo.33 It seemed that so successful a beginning of parish service at Saint Katherine’s Cathedral would open for Fr. John a new period in his priestly service. In this period, Fr. John’s pastoral inspiration and sacrificial demeanor, so characteristic of him in his former activity, might be combined with the daily routine of the outward conditions of his service and with the spiritual and harmonious personal relationships between a diligent pastor and his numerous pious flock. But the cataclysms of the February Revolution that burst out in Petrograd just three months after Fr. John’s assignment to Saint Katherine’s began little by little to involve Tsarskoye Selo in the treacherous vortex of revolutionary events.

The soldiers’ riots that had taken place in the military headquarters at Tsarskoye Selo already during the first days of the Revolution, and the imprisonment of the royal family at Alexandrovsky palace over a period of many months, brought the town to the attention of representatives of the most extreme revolutionary elements. These circles had propelled the country toward the path of civil war, and eventually, complete internal political division, the beginnings of which lay in Russia’s participation in the bloodshed of World War I. These developments gradually changed the quiet atmosphere of Tsarskoye Selo, diverting the inhabitants’ attention from the conscientious fulfillment, day by day, of their Christian and civil responsibilities to Church and fatherland. And during all these troubled months the inspiring message of Fr. John continued to sound forth from the ambon of Saint Katherine’s Cathedral, as he strove to instill feelings of reconciliation into the souls of the Orthodox Christians of Tsarskoye Selo, calling them to the spiritual perception of their own inner life, so that they might understand the contradictory changes taking place in Russia.

For several days after the October 1917 seizure of power by the Bolsheviks in Petrograd, reverberations from the momentous events happening in the capital were felt in Tsarskoye Selo. Attempting to drive Gen. Paul Krasnov’s Cossack troops, which were still loyal to the Provisional Government, out of Tsarskoye Selo, the armored groups of the Red Guard — the soldiers and sailors supporting the Bolshevik upheaval — were coming there from Petrograd. On the morning of October 30, 1917, stopping at the outskirts of Tsarskoye Selo, the Bolshevik forces began to expose the town to artillery fire. The inhabitants of Tsarskoye Selo, like those in all of Russia, still did not suspect that the country was involved in a civil war. A tumult erupted, with many people running to the Orthodox churches, including Saint Katherine’s, in hopes of finding prayerful serenity at the services, and of hearing from the ambon a pastoral exhortation pertaining to the events taking place. All the clergy of Saint Katherine’s Cathedral eagerly responded to their flock spiritual entreaties, and a special Moleben, or prayer service, seeking an end to the civil conflict, was offered beneath the arches of the church, which was jammed with worshippers. Afterwards, the dean of the Cathedral, the archpriest N. Smirnov, together with two other priests, Fr. John and Fr. Steven Fokko, reached a decision to organize a sacred procession in the town, with the reading of fervent prayers for a cessation of the fratricidal civil strife. The pages of the newspaper All-Russian Church Social Messenger presented, for several days, the testimony of a certain Petrograd newspaper correspondent describing the events which had taken place, as follows: “The Sacred Procession had to be relocated under the conditions of an artillery bombardment, and notwithstanding any predictions it was rather crowded. The lamentations and cries of women and children drowned out the words of the peace prayer. Two priests delivered sermons during the procession, calling the people to preserve tranquility in view of the impending trials. I was fortunate enough to understand clearly that the priests’ sermons did not contain any political tinges.”

The Holy Procession lingered. Twilight changed into darkness. Candles were lit in the hands of the praying people. Everybody was singing.

Precisely at that time the Cossacks were withdrawing from the town. The priests were warned about it. Isn’t it time to stop the prayers?! We shall carry our duties to completion, they declared. These have departed from us, and those who are coming are our brothers! What kind of harm will they do us?!34

Wishing to prevent an outbreak of fighting in the streets of Tsarskoye Selo, the Cossack leadership began to withdraw troops from the town on the evening of October 30, and on the morning of the 31st the Bolshevik forces entered Tsarskoye Selo, encountering no opposition. One of the anonymous witnesses to the aftermath of these tragic events wrote a letter to the prominent Saint Petersburg Archpriest F. Ornatsky, who himself was destined to receive martyrdom at the hands of the godless authorities. The writer told in simple but profound words of the passion-bearing that became the destiny of Fr. John. Yesterday (on October 31), he wrote, when the Bolsheviks, together with the Red Guard, entered Tsarskoye Selo, they began to make the rounds of the apartments of the military officers, making arrests. Fr. John (Alexandrovich Kochurov) was conveyed to the outskirts of the town, to Saint Theodore’s Cathedral, and there they assassinated him because of the fact that those who organized the sacred procession had allegedly been praying for a victory by the Cossacks, which surely was not, and could not have been, what actually happened. The other clergymen were released yesterday evening. Thus, there has appeared another Martyr for the Faith in Christ. The deceased, though he had not been in Tsarskoye Selo for long, had gained the utmost love of all, and many people used to gather to listen to his preaching.35

The Petrograd journalist mentioned earlier reconstructed a terrifying picture of Fr. John’s martyrdom and its aftermath, ascertaining these details: The priests were captured and sent to the headquarters of the Council of the Working and Soldiers Deputies. A priest, Fr. John Kochurov, was trying to protest and to clarify the situation. He was hit several times on his face. With cheers and yelling the enraged mob conveyed him to the Tsarskoye Selo airdrome. Several rifles were raised against the defenseless pastor. A shot thundered out, then another, after which the priest fell down on the ground, and blood spilled upon his cassock. Death did not come to him immediately . . . He was pulled by his hair, and somebody suggested, “Finish him off like a dog.” The next morning the body was brought into the former palace hospital. According to the newspaper The Peoples’ Affair, the head of the State Duma, together with one of its members, saw the body of the priest, but the pectoral cross was already gone from his breast . . .36

This latter circumstance accompanying Fr. John’s martyrdom, as mentioned by the reporter, takes on a particular spiritual significance when viewed against the background of some words spoken by Fr. John twelve years before his death, which proved to be prophetic. In faraway America, when he received his gold pectoral cross at the ceremony marking the tenth anniversary of his priestly service, he said with emphasis, “I kiss this Holy Cross, a gift of your brotherly love for me. Let it be my support in times of tribulation. I will utter no pathetic comments about my intention not to be separated from it even till my grave: that would have a grandiloquent sound, but would not be prudent. It does not have any place in a grave. Let it remain here on earth for my children and posterity as a family Holy Relic, and as a clear proof that brotherhood and friendship are the most sacred things on the earth….”37

In this manner did Fr. John express his gratitude towards his colleagues and his flock, not suspecting that this very prayer about that brotherhood and friendship would descend on the Russian Orthodox people at a time when love and clemency were scarce in long-suffering Russia — provoking a pitiless hatred towards him from the side of the apostates, who deprived him of his earthly life and snatched away the pectoral cross from his chest, but were not able to rob him of the imperishable glory of Orthodox martyrdom.

At the beginning of November 1917, the Bolshevik power could not yet secure unfettered control even over the suburbs of Petrograd, and terror on a state level had not yet become an unavoidable part of Russian life. So, with the populace of Tsarskoye Selo and Petrograd in a state of complete horror and exasperation, this first malicious execution of a Russian Orthodox priest inspired the former organs of power, who were not yet ousted by the Bolsheviks, to form an investigating commission which included the two representatives of the Petrograd city council. It was soon abolished by the Bolsheviks, without having managed to identify Fr. John’s murderers.38

For Russian Church life, however, this first martyrdom of a Russian Orthodox pastor in the twentieth century was deeply significant. It aroused a profound spiritual response within the hearts of many laity, clergy, and hierarchy of the Russian Orthodox Church. The Church service for the departed and his burial in the crypt of Saint Katherine’s Cathedral in Tsarskoye Selo39 were served by the shocked local clergy in an atmosphere of great dismay and anxiety. At the time, the Most Reverend Benjamin, Metropolitan of Petrograd, the future Holy Martyr, was attending the All-Russian Church Council being held in Moscow. Within a few days after the burial, the leadership of the Petrograd diocese, with Metropolitan Benjamin’s blessing, published the following announcement in the newspaper All-Russian Church-Social Herald:

“On Wednesday, November 8, the ninth day after the death of Fr. John Kochurov who was murdered October 31 in Tsarskoye Selo, a hierarchical Panikhida will be served in Our Lady of Kazan Cathedral at 3 p.m. for the eternal memory of Archpriest John and of all the Orthodox Christians who have perished in a time of civil conflict. Parish clergy free of serving obligations are invited for the Panikhida. Vestments should be white.40

“Soon after this hierarchical Panikhida served in Our Lady of Kazan Cathedral, the diocesan council of Petrograd published a proclamation To the Clergy and the Parish councils of the Diocese of Petrograd. This became the first official recognition of the martyric character of the Fr. Johns death pronounced in the name of the Church, but also the first Church statement to specify concrete measures of assistance to the families of clergymen persecuted and assassinated by the theomachists in Russia. In this remarkable document of church history — eloquently expressed, with deep humility in the face of the anticipated future persecution of the Church, and embodying genuine sympathy for Fr. John’s bereaved family — the leadership of the Petrograd diocese reacted to the death of the first diocesan Holy Martyr:

“Dear brothers,” began the statement by the Petrograd diocesan council, “on October 31 of this year the town of Tsarskoye Selo suffered the martyrdom of one of the good shepherds of the Petrograd diocese, the Archpriest of the local Cathedral, John Alexandrovich Kochurov. Without any blame or justification for this on his part, he was seized in his apartment, conveyed to the suburbs, and was there, in an open field, shot by the possessed mob . . .

“It was with feelings of profound sorrow that the Petrograd diocesan council received this news; the grief has been considerably augmented by the realization that, with the Archpriest’s demise, a large family is left behind, consisting of six members who now are without food, shelter, or any means of subsistence.

“God is the Judge of the cunning villains who violently ended the life that was still young. Even if they flee unpunished from trial at the hands of men, they can never elude the judgment of God. But our obligation now is not only to pray for the peace of soul of this innocent sufferer, but with all our sincere love to attempt to treat the deep and incurable wound that has been inflicted on the very hearts of the poor bereaved family. The diocese and the diocesan clergy are directly obligated to provide for the martyred pastors orphaned family, to give them the opportunity to live in material comfort, and to provide the children with a proper education.

“The diocesan Church council, being moved by the loftiest of sentiments, now appeals to the clergy, parish councils, and all the Orthodox faithful of the diocese of Petrograd with an ardent entreaty, asking most earnestly, for the sake of Christ’s love, that you stretch forth a brotherly helping hand, and by whatever amount you can offer, support a poor family left to be at the mercy of fate. Great is the need, and it should not be delayed!

“. . . His martyrdom is, for each of us, a dire reminder, an ominous warning. We therefore must be ready for anything. And to prevent such situations of destitution as we now have, we must prepare, between the times of trial, an assistance fund to be allotted for the defenseless, persecuted, and tormented clergy that in such cases and in similar ones they may have material aid from their kindred in spirit.

“. . . Through the deans special lists will be sent to each parish in the diocese for the collection of donations, those that are voluntary and from the Church funds, for help to the family of the deceased Archpriest John Kochurov, and also for the establishment of the special fund for assistance to the clergy in all similar cases.

“. . . An immense task requires means commensurate with it. The diocesan Church council hopes that with God’s help such means will be found. The modest offering of the diocese and clergy, made voluntarily and laid on the Christian conscience of each person, will provide an opportunity for drying the tears of the unhappy orphans and for making a beginning of that concern for good brotherly assistance, for which our clergy have a great need particularly now . . .

“It has thundered; now is the time to make the sign of the Cross!”41

On one of his regular visits to his diocese during the All-Russian Church Council in Moscow, Metropolitan Benjamin served the Divine Liturgy on November 26, for the patronal feast at Saint Katherine’s Cathedral in Tsarskoye Selo. The Liturgy ended with a fervent exhortation from the hierarch, during which he appealed to the people for unity, love, and brotherhood, wrote a correspondent for the All Russian Church-Social Herald. The Metropolitan also mentioned the terrible event, the assassination of the beloved pastor of the local Church, Fr. John Kochurov; he noted that though it is a very sad occasion, it has been a cause of reconciliation as well, through the realization that the pastor had laid down his life for love of God and of neighbor, providing an example of martyrdom. The archpastoral message had a strong effect on everyone, and tears were seen on many faces. Following the Liturgy, the Litia for the departed took place at Fr. John’s tomb in the burial-vault of the cathedral. After the service the Metropolitan visited the rectory, where he met the family of the deceased.42 Thus, a second time — and now from the mouth of the diocesan hierarch, who remembered the slain clergyman of his diocese — the Russian Orthodox Church characterized Fr. John’s death as a martyrdom.

The All-Russian Church Council was just then taking place in Moscow, and this death had deeply touched the hearts of the delegates, arousing loud lamentation. Archpriest P. Mirtov was commissioned to compose a proclamation expressing the sense of the Council, giving information about the untimely death of the deceased Fr. John Kochurov, who fell victim while zealously fulfilling the obligations of his rank.43

The Most Holy Patriarch Tikhon had become well acquainted with Fr. John during the many years they worked together in the diocese of North America and the Aleutians, and felt therefore a deep respect for him. Expressing a genuine conviction formed at the Council that the Russian Orthodox Church had gained a new martyr saint in the event of Fr. John’s death, the Patriarch dispatched a letter of sympathy to Alexandra Kochurova, the deceased pastor’s widow: “With great sadness the Most Holy Council of the Russian Orthodox Church has received a report concerning the martyrdom of Father John Alexandrovich Kochurov, who has fallen victim while zealously fulfilling the obligations of his rank,” wrote the future Confessor, the Most Holy Patriarch Tikhon. “Joining our prayers with those of the Holy Council for the repose of the soul of the slain Archpriest John, we share your great grief, and we do that with a special love, because we knew well the deceased Archpriest, and have always held his inspiring and strong pastoral activity in high estimation.

“We bear in our hearts the sure hope that the deceased pastor, adorned with the wreath of martyrdom, now stands at the Throne of God among the elect of Christ’s true flock. The holy Council, with earnest sympathy for your bereaved family, has decided to petition the Holy Synod to give you the proper assistance.

“May the Lord help you to endure the trial sent to you by the ways of God’s Providence, and preserve you and your children unharmed amid the storms and calamities of our time.

“We invoke God’s blessing on you and on your family. Patriarch Tikhon.”

Exactly five months after Fr. Johns death, on March 31, 1918 — by which time the number of murdered clergymen known to the Holy Synod had already reached fifteen — the first Memorial Liturgy for the New Hieromartyrs and Martyrs in the history of the Russian Orthodox Church in the twentieth century was served in the church of the Moscow Theological Seminary, by the Most Holy Patriarch Tikhon, four other hierarchs, and ten archimandrites and protopresbyters. At the Memorial Liturgy and Panikhida, when the supplicatory prayer was pronounced for the repose of the servants of God who have perished for the Faith and the Orthodox Church, following mention of the first slain hierarch, Metropolitan Vladimir, the first-slain Archpriest, Father John Kochurov, was remembered, who by his passion-bearing death ushered in the service offered by the confessors, the assembly of the Russian New-Martyrs of the twentieth century.45

Sources and Literature

1. The central state historical archive of Saint Petersburg (CSHA of S.-P.), F. 14 University of Petrograd, 3, f.31575, the personal folder of the student Dmitry Alexandrovich Kochurov.

2. CSHA of S.-P., F.19 The Church Consistory of Petrograd, 113, f.4167, the clergy list of the Holy Transfiguration cathedral in Narva from 1908, f.4333; ibid. from 1916, f.4366, the clergy list of the Saint Katherine cathedral in Tsarkoye Selo.

3. CSHA of S.-P., F.139 the Office of the dean of the department of education of Saint Petersburg, 1, f.11305, the annual assessment of the condition of the male gymnasium in Narva from 1908.

4. CSHA of S.-P., F.277 Saint Petersburg Theological Academy, 1, f.3220, the lists of the seminarians come to the examinations in the Saint Petersburg Theological Academy in August of 1891.

5. American Orthodox Messenger (until 1898 The Orthodox American Messenger), 1896, NN1, 7; N14; 1898, N24; 1899, N11; 1900, N10; 1901, N1; 1902, N8; 1904, N5; 1905 N17; 1906, NN10,11; 1907, N14.

6. Vserosiysky Tserkovno-Obschestvenniy Vestynik, 1917, 2 Nov., 5 Nov., 1 Dec., 15 Dec.

7. Pribavleniye k Tserkovnim vedomostyam, 1918, N5-16.

8. Tsarskoselskoye Delo, 1916, 18 Nov.

9. Tserkovniye vedomosty, 1912, N18; 1916, N18-19; 1917, N48-50; 1918, N15-16.

10. Circulars of the Department of Education of Saint Petersburg from 1907.

11. Maltsev, A. The Orthodox Church and Russian establishments abroad (in Russian; Saint Petersburg, 1906).

1The central state historical archive of Saint Petersburg (CSHA of S.-P.), F. 14,3, f. 31575, 1.8, 10.

2CSHA of S.-P., F. 277, 1, f. 3220, par. 1,2,3,4,5,6,8.

3CSHA of S.-P., F. 19, 113, f. 4167, par. 37.

4American Orthodox Messenger (AOM), 1907, N14, p. 269.

5SCHA of S.-P., F. 19, 113, f. 4167, par. 37.

6AOM, 1898, N24, pp. 681-682.

7AOM, 1896, N7, p. 117.

8AOM, 1898, N24, p. 682.

9Ibid.

10AOM, 1897, N14, p. 290.

11AOM, 1900, N10, p. 215.

12AOM, 1896, N1, p. 14; CSHA of S.-P., F. 19, 113, f. 4167, par. 38-39.

13AOM, 1898, N24, p. 682.

14AOM 1899, N11, pp. 305-306.

15AOM, 1901, N1, pp. 26, 32.

16AOM, 1902, N8, pp. 171-173.

17A. Maltsev. The Russian Orthodox churches and institutions abroad. Saint Petersburg, 1906, p. 419 (in Russian).

18AOM, 1905, N17, pp. 340-341.

19CSHA of S.-P., F. 19, 113, f. 4167, par. 40.

20AOM, 1904, N5, p. 81.

21AOM, 1905, N17, pp. 340-342.

22AOM, 1906, N10, p. 206.

23AOM, 1906, N11, p. 229.

24AOM, 1907, N14, pp. 269-270.

25CSHA of S.-P., F. 19, 113, f. 4167, par. 37.

26Circular of the Department of Education of Saint Petersburg, from 1907, p. 294.

27CSHA of S.-P., F. 139, 1, f. 11305, par. 28.

28Tserkovniye vedornosty, a newspaper, 1912, N18, p. 128.

29Ibid., 1916, N18-19, p. 167.

30CSHA of S.-P., F. 19, 113, f. 4333, p. 12.

31Tsarskoselskoye Delo, 1916, 18 Nov.

32CSHA of S.-P., F. 19, 113, f. 4366, 1.20.

33Vserosiysky Tserkovno-0bschestvenniy vestnik (VTOV), 1917, 5 Nov.

34Ibid.

35Ibid.

36Ibid.

37AOM, 1905, N17, pp. 340-342.

38VTOV, 1917, 5 Nov.

39VTOV, 1917, 1 Dec.

40VTOV, 1917, 7 Nov.

41Tserkovniye vedomosty, 1917, N48-50. pp. 2-3.

42VT OV, 1917, 1 Dec.

43VTOV, 1917, 2 Nov.

44VTOV, 1917, 15 Dec.

45Pribavleniye k Tserkovnym vedomostyam, 1918, N15-16, p.519.

Read about more Saints of North America