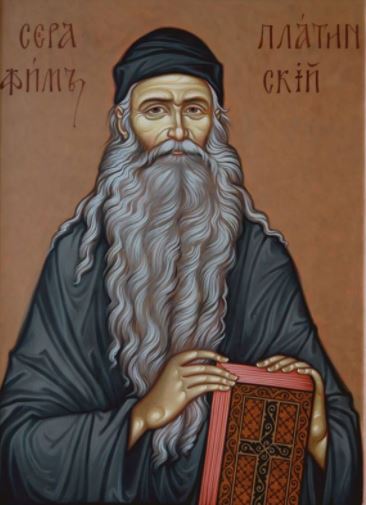

Hieromonk Seraphim (secular name Eugene Dennis Rose; August 13, 1934 – September 2, 1982) was a hieromonk of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia in the United States, whose writings have helped spread Orthodox Christianity throughout modern America and the West and are also quite popular in Russia, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece. Although not formally glorified (canonized), he is celebrated by some Orthodox Christians as a saint in iconography, liturgy, and prayer.

Early life

Eugene Rose was born on August 13, 1934, in San Diego, California. His father was Frank Rose, a World War I veteran. Eugene’s mother Esther Rose being a businesswoman was also a California artist who specialized in impressionist renderings of Pacific coast scenes. Raised in San Diego, Eugene would remain a Californian for the rest of his life. His older sister was Eileen Rose Busby, an author, MENSA member, and antiques expert; his older brother was Frank Rose, a local businessman. Rose was also an uncle of scientist and author J. Michael Scott, true crime author and journalist Cathy Scott, and Cordelia Mendoza, antiques expert and author.

Rose was baptized in the Methodist faith at fourteen years old, but later became an atheist, losing all belief in God. After graduating from San Diego High School, Eugene attended Pomona College, where he studied Chinese philosophy and graduated magna cum laude in 1956. While at Pomona, Rose was a reader for Ved Mehta, a blind student who would go on to become a well known author. Mehta referred to Rose in two books, one of which was Stolen Light, a book of memoirs: “I felt very lucky to have found Gene as a reader. … He read with such clarity that I almost had the illusion that he was explaining things.” Afterward, Rose studied under Alan Watts at the American Academy of Asian Studies before entering the master’s degree program in Oriental languages at the University of California, Berkeley, where he graduated in 1961 with a thesis entitled ‘Emptiness’ and ‘Fullness’ in the Lao Tzu.

In addition to a remarkable gift for languages, Rose was also known for possessing an acute sense of humor and wit. He enjoyed opera, concerts, art, literature, and the other cultural opportunities richly available in San Francisco, where he settled after his graduation and explored Buddhism and other Asian philosophies.

Orthodoxy

While studying under Alan Watts at the American Academy of Asian Studies after graduating from Pomona College in 1956, Eugene discovered the writings of René Guenon. Through Guenon’s writings, Eugene was inspired to seek out an authentic, grounded spiritual faith tradition. In the summer of 1955, between his junior and senior years at college, Eugene met Finnish-born Jon Gregerson, through whom he came into initial contact with the Orthodox faith. Eugene came out as homosexual to a close friend from college after his mother discovered letters penned between her son and Walter Pomeroy, a friend from high school. Gregerson, a practicing Russian Orthodox Christian at the time, introduced Eugene to Orthodoxy. Just as Gregerson was choosing to abandon his Orthodoxy, Eugene was inspired to learn more about the faith. Eugene later shed his identity as a gay man as he slowly accepted Orthodoxy, eventually ending his lengthy relationship with Gregerson.[1] This culminated in Eugene’s decision to enter the Church, being received into the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia through chrismation in 1962.

Eugene and another Orthodox Christian, Gleb Podmoshensky, later formed a community of Orthodox booksellers and publishers called the St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, with the blessing of St. John Maximovitch, Archbishop of San Francisco in the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. The community eventually decided to flee urban modernity into the wilderness of northern California to become monks in 1966. At his tonsure in 1970, Eugene took the name “Seraphim” after St. Seraphim of Sarov.

Following his ordination as hieromonk, Fr. Seraphim began writing several books, including Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future, and The Soul After Death. One of his best known books, God’s Revelation to the Human Heart, was originally given as a lecture to a religious studies class at UC-Santa Cruz in 1981, and published in book form after his repose. He also founded the magazine The Orthodox Word, still published today by the Brotherhood. The collective body of work that Fr. Seraphim published quickly proliferated throughout America upon Fr. Seraphim’s death and later in Russia and Eastern Europe upon the fall of atheist Communism in those countries, though typewritten copies of some of his books had been distributed underground for many years prior.

As a layman in San Francisco, the future Fr. Seraphim developed a close relationship with his spiritual father and mentor, St. John Maximovitch (+1966), then Archbishop of San Francisco for the Russian Church Abroad.

Teachings

Although an American convert, Fr. Seraphim is regarded by many as a bastion of sound Orthodox teaching in a time when many American jurisdictions, and even factions within the Russian Church Abroad itself, were allegedly introducing new and/or erroneous teachings or practices. In Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future, Fr. Seraphim highlighted what he and others saw as dangerous trends in both the secular and ecclesiastical worlds—namely, modernism and ecumenism (though the book mainly deals with religious movements invading America and outside Orthodoxy).

It was during this time also that Holy Transfiguration Monastery (Brookline, Massachusetts) began to distort the official positions of the Synod of the Russian Church Abroad[citation needed]. Fr. Seraphim with his fellow monastic, Fr. Herman (Podmoshensky), used their own tiny printing press to transmit what they regarded as the uncompromised teachings of the Church on a number of issues such as evolution, life after death, and pre-Schism western saints.

One major issue of contention between Fr. Seraphim and Holy Transfiguration Monastery was the presence of grace within the allegedly Soviet-compromised hierarchy of the Moscow Patriarchate. Fr. Seraphim refuted the extremist views of this monastery and consistently affirmed that Moscow, though ailing, still had grace.

Throughout his life, Fr. Seraphim stressed an “Orthodoxy of the heart,” which he felt was absent in much of the ecclesiastical life in America.

One of his more controversial books is The Soul After Death, which includes the teaching which had been passed on to Fr. Seraphim from Saint John of the so-called Aerial Toll-Houses, regarding the soul’s journey after its departure from the body. This teaching has drawn criticism from some within the Orthodox Church, but has been defended by such noted theologians as Metropolitan Hierotheos (Vlachos) and Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov).

Death

After feeling acute pains for several days while working in his cell in 1982, Fr. Seraphim was taken by his fellow monks to a hospital for treatment. When he reluctantly arrived at Mercy Medical Center in Redding, California, he was declared in critical condition and fell into semi-consciousness. After exploratory surgery was completed, it was discovered that a blood clot had blocked a vein supplying blood to Fr. Seraphim’s intestine, which had become a mass of non-functioning dead tissue. Fr. Seraphim slipped into a coma after a second surgery. Hundreds of people came to visit the hospital and celebrated the liturgy regularly in the chapel, praying for a miracle to save their beloved father’s life. Reaction from throughout the world was great, with thousands of prayers said for the ailing hieromonk. He died on September 2, 1982.

After being dead for several days and while lying in repose in a pauper’s coffin at his wilderness monastery, visitors claimed that Fr. Seraphim did not succumb to decay and rigor mortis. His body remained supple while several claimed he smelled of roses. A cause for glorification was begun after Fr. Seraphim’s burial. He eventually informally attained the title of Blessed after several miracles were attributed to him and now he awaits glorification into sainthood by an Orthodox synod.